The legacy of Tony Bettenhausen, Jr.

| By Earl Ma | |

| Sweet Sixteen The legacy of Tony Bettenhausen, Jr.

| |

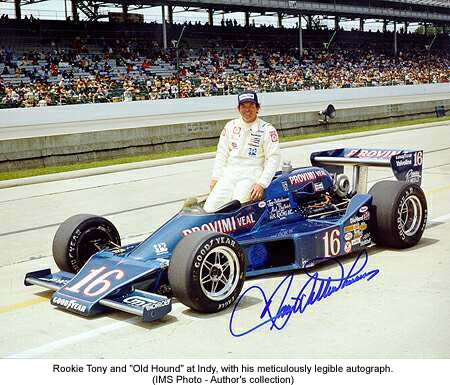

As the half dozen CART teams on hand for another pre-season test toiled at Sebring on February 21, all activity rolled to a stop as the paddock observed a 16 minute period of silence - in honor of the man responsible for the number 16 car's presence that day. And while the field began its first official day of practice Friday before the season opener at Homestead, CART Ministries prepared for a special memorial service that afternoon - dedicated to the man whose family and friends ensured the 16 car would participate in Miami and beyond. Tony Bettenhausen bridged the increasingly tenuous gap between traditional American oval track open wheel racing, where his fabled family first rose to promience, and the modern-day emphasis on road course racing where CART thrives. He made the long, difficult transition from being an Indycar driver of reasonable aptitude to a popular and well-respected team owner capable of greater on-track success. While his first Champ Car win remained elusive nonetheless, he established an indelible legacy that the racing community - on both sides of the CART/IRL standoff - cannot obliterate. By the time Tony Lee Bettenhausen's big-league racing career took off with his Winston Cup debut in the 1974 Daytona 500, the family name had already become synonymous with the full spectrum of triumph and tragedy. Tony, Sr., nicknamed the "Tinley Park Express" after his suburban Chicago hometown, won the 1951 AAA National Driving Championship soon after Tony, Jr.'s birth, repeating the feat under USAC sanctioning in 1958. While he perennially went into the month of May as an Indy 500 favorite, he could never quite pull the feat off. In 1961, driving for Lindsey Hopkins, Tony, Sr. again had an excellent chance at victory. But on the day before qualifying began, with his good friend Paul Russo struggling with an ill-handling Watson, he graciously offered to take the car out on a shakedown run and see if he could help Russo get up to speed. He never came back, having hurtled into the frontstretch wall at lethal velocity and becoming entangled in the catch fence in flames by a broken steering bolt. Of the three Bettenhausen boys, eldest son Gary soon became an open wheel legend in his own right, thanks to many memorable dirt track duels with Larry Dickson. By 1972, he found himself driving alongside Mark Donohue in the Penske squad as it began skyrocketing towards dynastic status. Gary dominated the 500 that year, leading 138 laps, and seemed well on his way to victory when his ignition failed. He watched disconsolately as his teammate inherited the honors instead. Middle brother Merle passed his rookie test at the Brickyard that same year but made no qualifying attempt. Later that summer, on the opening lap of his Indycar debut at Michigan International Speedway, he crashed on the backstretch and caught on fire. As he hastily tried escaping from the flames, he stuck his right arm out of the cockpit with the car still in motion. The Armco barrier promptly removed his arm. These disasters did not faze Tony, Jr. as he began racing himself, finishing second in NASCAR's Sportsman division in 1972 and earning "Most Popular Driver" honors. With sponsorship from longtime Indycar benefactor (and stepfather) Gordon Van Liew, he attempted the full Winston Cup schedule two years later, making 27 of the 30 races (out of 33 career starts) and placing a promising 20th in final points, with one top ten finish to his credit. But instead of continuing in NASCAR, Tony then returned to his roots and competed for the next several years (with minimal success) in sprints and midgets on the midwestern bullrings which had brought his father and brothers great acclaim. One of those tracks - Syracuse in New York - nearly finished Gary off in 1975, when a violent end-over-end tumble resulted in permament nerve damage to his left arm (and in getting fired while still hospitalized by Penske - a move from which his career never fully recovered). Merle, who had resumed driving sprints with a hook attached to the steering wheel, had enough and finally retired. By all accounts, Tony's tenure in the sprints and midgets did not get him very far, and he struggled with the transition from stock cars. Most significantly during this period, he married Shirley McElreath, the daughter of longtime Indycar regular Jim McElreath. The couple met at a Houston Astrodome sprint race held at the Houston Astrodome, and when CART debuted in Houston in 1998, Tony never appeared in the pits or paddock without wearing an Astros baseball cap. His in-laws' family also came with tragic undertones, with Shirley's kid brother James poised to join the senior McElreath as the first father and son competing head-to-head at Indy in 1977. But James missed the show in his AMAX Coal-sponsored Eagle and then perished in a sprint car wreck at Winchester, IN later that summer. Months after the formation of CART in early 1979, Tony finally made his way to the Brickyard as a driver. He made no qualifying attempt that year (although he drove in five USAC Indycar races and earned Rookie of the Year honors) and got bumped in 1980. So his prospects for 1981 did not look much brighter when he showed up with an ancient ex-Tom Sneva flat-bottomed McLaren M24, carrying the number 16 and nicknamed "Old Hound." Run by Wayne Hillis and Jack Rodgers under the H&R Racing banner, the motley team, led by veteran wrench Paul Diatlovich, rented space out of A.J. Watson's shop. Tony surprised his detractors by qualifying 16th and finishing 7th amid a bumper crop of rookies despite a mid-race collision with doomed Gordon Smiley. It would be his best result in eleven 500 appearances. He also convinced Dutch businessman Aat Groenvelt and his Provimi Veal company, which came aboard after qualifying, into bankrolling the operation for the rest of the season. With that, Tony became another bona fide Indianapolis success story. 1981 also marked his best career year as a CART driver, placing 6th in final points and earning the "Most Improved Driver" award. At the inaugural Michigan 500 that summer - the same track which savagely ended brother Merle's career - Tony finished 2nd in "Old Hound" behind fellow second-generation driver Pancho Carter, but a still-controversial scoring snafu convinced many that Tony had actually won his one career Indycar win that day. Supposedly CART scorers mistakenly docked Tony one lap, and Tony actually finished a full lap clear of Carter. Tony and others also alleged Carter received an illegal push-start in the pits for which he was never penalized. "No, we were paid for second," Tony told writer Jep Cadou in 1986, contrary to rumors suggesting CART paid him and Carter first place money. "And I knew they would never change the standings because that was 1981, the year in which it took USAC until October to decide who had won the Indianapolis 500." He claimed CART would not even allow his team to file a formal protest. Groenvelt and Provimi upped the financial ante in 1982 and became the full-fledged owners in 1983, but Tony could not match his rookie year's performance. In late 1983, Provimi expanded to a two-car effort by adding rookie Derek Daly to the stable after the latter's deal with the Wysard team collapsed. While the Irish F1 veteran's involvement in the team helped Tony improve his own road course racing skills, Tony soon fell from favor within the Provimi organization and only raced the following year at Indy and Pocono for them. In such a situation, many downsized people may feel animosity towards the "new guy," but certainly not in this case. "Tony was one of the most giving people I have ever met," Daly remembers. "He embraced myself and my family as soon as we all met. My mother loved him, and while in Ireland two years ago, Tony and Shirley took my parents out for dinner. "I have great memories of racing with Tony in 1983-84, running around the country, playing golf, partying, flying ultra-light aircraft and just enjoying life. He was a joy to be with." With Daly injured in late 1984 with a nasty crash of his own at Michigan, Groenvelt soon turned his full attention towards a young Dutch Super Vee graduate named Arie Luyendyk, leaving Tony unemployed and scrambling for a 500 ride. He eventually landed in a backup Dan Gurney-Mike Curb Lola via a partnership deal again involving Hillis and Rodgers, among others (including dairyman Russ Roberts, also aboard Tony and Shirley's ill-fated flight), who came up with $110,000 within a 48-hour period. Tony then sweated out the final 40 minutes of qualifying on the bubble. After finishing 29th, Tony and his partners sold the car back to Gurney and Curb for the same amount. "I think Mike Curb and his connection with Cary Agajanian at the time made that (happen)," says Gurney. I think US Tobacco at the time - Skoal was involved (as primary sponsor). But I wasn't directly involved with the minuteae. I was quite happy and willing to help out where we could. I felt that Tony was a very deserving young driver, and if we had the opportunity, we were going to take it." Tony vowed he would not go into May so unprepared again. With a coalition of 43 friends and Indianapolis businessmen backing him, he came up with enough money for a new March 86C and became an owner-driver, qualifying a solid 18th but breaking early. The $77,000 he earned that day went into paying for next year's car, while the 86C got leased out to Groenvelt and Luyendyk. He then spent the rest of 1986 at his new "day job," selling cars at the Greenwood, IN Stuart-Skillman Oldsmobile dealership which sponsored him for the 500. Thus marked the formal beginnings of Bettenhausen Motorsports. The following year at Indy, Tony finished an encouraging 10th but saw a loose wheel from his car being punted into the grandstands, where it killed spectator Lyle Kurtenbach. Kurtenbach's family sued the team as well as Goodyear and Indianapolis Motor Speedway, eventually settling out of court for an undisclosed amount. This tragedy could easily have shut down teams run by men of lesser resolve. After having competed at Indy only for the previous three years, Tony gradually found enough funding to return to a partial schedule in 1988, purchasing a CART franchise. A good portion of this funding originated from drivers bringing sponsorship in exchange for rides, beginning the tradition of Bettenhausen Motorsports as a starting point for many cosmopolitan names looking for their first break into the Indycar ranks.

Those who have driven for Bettenhausen over the years include Dennis Vitolo, Michael Greenfield, Cor Euser (10th at the 1990 Laguna Seca race in his only career Indycar appearance), Stefan Johansson, Robbie Groff, Gary Brabham, Scott Sharp, Patrick Carpentier, Roberto Moreno, Helio Castro-Neves, Shigeaki Hattori and Gualter Salles. Andrea Montermini, while never competing for Tony, stayed at the Bettenhausens' home and tested for the team last summer; Tony's personal recommendation went a long way towards Gurney hiring Montermini for the latter road course events in 1999. As the years progressed, so did Tony's ability to attract bigger sponsorship, in contrast to the team's lean early years which netted token dollars from the likes of Yugo of America and Federal Truck Driving School. The real money began rolling in with AMAX, the energy company which had sponsored James McElreath's failed 1977 500 attempt. With bigger sponsorship came better equipment (such as brand-new Penskes with factory support in the mid-1990's) and bigger talent. After Tony frustratingly missed the show at Indy in 1992, he skipped the track on race day, opting for a soul-searching motorcycle ride instead. He returned home with a newfound commitment to his fledgling team - one which meant easing himself out of the cockpit. Two weeks later, at the next CART event at Detroit, F1 veteran Stefan Johansson - with many podiums but no wins for the likes of Ferrari and McLaren - got his first taste of Indycar racing behind the wheel of the #16 car. Johansson, similarly at a career crossroads, finished a remarkable third, then equaling the record for the highest debut finish in CART history. Despite only running 9 of the 16 races on the schedule, Johansson (Tony's first ever paid driver, bringing no sponsorship to the team) tied for 13th in season points and easily won Rookie of the Year honors. "Tony is just the straightest guy to work with," Johansson told Bones Bourcier in an early 1995 Indy Car Racing interview. "There are no secrets. When I meet with him, and we're negotiating, I don't go in there thinking, 'well, I'd better hit him with this, because he's going to come back with that. I just say, 'here's what I want,' and he says, 'here's what we've got to work with.' He shows me every figure, every contract with every sponsor. There's no mind games with us. It's just a 100 percent, straight dialogue."

Johansson's ALMS and former Indy Lights shop operates just a few doors away from Bettenhausen Motorsports. He now reiterates, "Tony was the most straight-forward, honest car owner I ever drove for," "In a time like this, we tend to think of life in terms of months and years. But I think in Tony's case, it was more the quality of life he lived during those years he had." "I had mixed emotions at Detroit," Tony told Indy Car Racing's Ned Wicker that July. "I'd like to be in this business a long time. If we as owners can get a hold of costs of the sport, maybe I can hang around a few more years. Let's face it, I'm forty years old; there are a lot of young guys out there, a lot of young fighters. Frankly, I admire A.J. Foyt and Mario Andretti for driving up into their fifties, but I don't have a particular interest in doing it. "I had a sneaking suspicion we would be competitive. It was better than what I had possibly imagined, but I don't kid myself. The first five years that I sat in a race car, from when I was 17 until I was 22, I never turned right intentionally. The Stefans, the Derek Dalys, they are used to European racing where they turn right as much as they turn left. Certainly Little Al and Michael (Andretti) and guys like that are competitive and can run with anybody I think from Europe. I am from a bit before them, and I am not as competitive as some of those guys and the Stefan Johanssons, so that is why I am probably not going to do anymore road courses, certainly this year. What is going to happen in 1993, I am not quite sure yet." Indeed, Tony effectively retired as a driver after the 1993 Indy 500, which also marked brother Gary's last 500 appearance and Johansson's first. From this point on, he became a full-time owner, brimming with newfound confidence and enthusiasm. But the much-anticipated first win for Johansson never came. Johansson retired from open wheel racing after the 1996 season, during which Tony fielded a second car for big brother Gary in the inaugural US 500 for Gary's final appearance in an Indycar.

While Gary has since held consultant roles for various IRL teams at Indy, Tony never wavered in his outspoken support of CART and the organization's continuing boycott of the 500. Some factions in Indy regarded him as a heretic turning his back on the Bettenhausen family legacy. Gurney returned to CART during the first season of the IRL, after a decade away from open wheel racing. "We were kindred spirits in many respects. We're still cognizant of the nostalgia - the historical element of that great institution back there. Certainly he even more than I was because of his dad, but nevertheless, we were both students of that element." But just like the man who authored the "White Paper" leading to the formation of CART, Tony never let those who threw their full support behind Tony George sway his own opinions. Without the carrot of Indy dangling before him, Tony focused his efforts on building his team, hiring reigning Toyota Atlantic champ Patrick Carpentier in 1997 and scoring another ROTY title. Carpentier also came tantalizingly close to scoring a win, letting Paul Tracy by late during the inaugural event at Gateway while in fuel conservation mode and cruising home second. "I have many fond memories of my season with the Bettenhausen team, and my podium at Gateway that year is definitely one of the most memorable moments of my career," Carpentier recalls. "That day was quite exceptional for us because it was the first trip to the podium, both for me and for the team. During my year at Bettenhausen, I got to know Tony's friends and family and my thoughts are with them as they try to cope with the loss of two of the finest people I've ever had the pleasure to work with." But Carpentier could not refuse an offer from Player's Forsythe for 1998, which sent Tony looking for his third driver in as many years. He came up with another gem in rookie Helio Castro-Neves, who came oh so close at Long Beach - in only his third career start - leading comfortably midway through the event before losing concentration and skidding off course with just 15 laps to go, finishing a heartbreaking 9th. He redeemed himself with an excellent runner-up finish at Milwaukee. Rick Shaffer served as Bettenhausen Motorsports' PR director for six years during the team's glory years, and he attests to the popularity and visibility of Tony the car owner in the CART paddock. "I will always remember that he had one of the neatest autographs for a celebrity I had ever seen. I asked him about that and he said, 'well, years from now, I want them to be able to read my name." I also asked him how he felt about autographs. He replied: 'it will bother me when they stop asking for autographs.'" By this time, Tony had assembled a small but loyal core of dedicated supporters within the team, with little turnover from season to season compared to other operations. Besides himself, the two key players behind the scenes remained his friend Russ and his better half. "Russ Roberts has been involved with my team since the early '80's," he told Wicker in 1992. "Russ does the tax end of the business; you know, the accounting, payroll - Russ takes care of all of that. He carries the owner card when I have a driver's license. "Shirley ... is probably the closest confidant I have ... she has been there with the tears; she has been there with the cheers, (1991) after a decent run in Michigan. She is always at the races with us ... the kids - we enjoy in the summer time having (daughters) Bryn and Taryn coming to the races with us ... I am relieved I don't have any boys so maybe I won't have to worry about race drivers." Besides her involvement with the team, Shirley became a pivotal figure in the day-to-day activities of CARA (Championship Auto Racing Auxiliary), the charitable support organization run by CART and IRL spouses. But after a decade of steady progress, the team's fortunes took a noticable downturn in 1999, with longtime sponsor Alumax (having merged with AMAX in 1994) becoming a merger victim itself and leaving the sport. Tony reluctantly released Castro-Neves at the 11th hour and wound up with the well-sponsored Hattori, resulting in one well-documented catastrophe after the other. Despite these setbacks, Tony retained his trademark sense of humor.

Shaffer has two favorite examples of Tony's ever-present wit. "Tony knew I had a fear of flying in planes so he often teased me. I also enjoyed taking Amtrak trips for the long-distance races because I thoroughly enjoy rail travel. Of course, every time there was an Amtrak accident, he would be the first to remind that even trains were not safe. "He also liked to tease me over my choice of restaurants. One year in Monterey, I had eaten at a fast-food place. The next day, he asked me where I had eaten dinner. When I told him, he replied: 'Shaffer, eating at a fast-food restaurant in Monterey, California, is like a pig wearing a Rolex.'" Tony's optimism paid off with very promising prospects for the 2000 season. The team which struggled in just keeping its doors open without adequate sponsorship a year ago welcomed a renewed commitment full- from both Reynard and Mercedes-Benz for the full year, and with veteran Michel Jourdain, Jr. bringing his Herdez sponsorship into the fold. The team went through the Spring Training routine at Homestead, and then Tony, Shirley, Russ, and team caterer Larry Rangel - relatively new to the team's inner circle but warmly welcomed from day one - began the flight home to Indy aboard Tony's Beechcraft Baron. Gurney aptly sums up the collective feelings of his fellow car owners and everyone else in CART. "(Tony) had a great, steadying influence on the CART community. He always had a very active sense of humor, and yet he was focused ... it just seems like these things happen to the ones that least deserve it. I'll miss him a lot - although I'm not involved with CART anymore, I was hoping he would do well. "As far as Shirley went, she was always very special too. They made a great couple. The Bettenhausen family has had more than their share of awkward and difficult circumstances. I don't know the answer...I know we'll miss them all." With Gary Bettenhausen embarking on a new career as a housing developer, middle brother Merle suddenly finds himself thrust back into the limelight after many years on the sidelines. Now workng as a manager and trainer at the same Skillman dealership where Tony worked in 1986 while launching Bettenhausen Motorsports, Merle has been named chief executor and custodian of his brother and sister-in-law's estate. With Bryn now in her first year at art school in Chicago and Taryn in middle school, Merle and his family cheerfully look after the girls as their own. Meanwhile, Russ Breeden and Jack Rogers - the nucleus of the original H&R Racing - and Merle vow they well keep the team going as Tony would have wished. "My mom said, 'it's hard losing two Tony Bettenhausens in one lifetime,'" Merle told RPMTonight in February. For younger - even much younger - generations following Indycar racing, they can also find the poignant truth in that assessment. | |||

| ©2000 Earl Ma and SpeedCenter

|

|

| |